A daily dose of odds and sods, some interesting, some bizarre, some funny, some thought provoking items which I have stumbled across the web. All to be taken with a grain of daily salt!!

Friday, December 25

Has the Kalki avatar already been born in the form of Prophet Mohammad or Mirza Ghulam Ahmad?

"Mirza Ghulam Ahmad claims “Krishna... appeared as a Prophet in India... I am the Krishna whose advent the Aryas are awaiting in this age. I do not make this claim on my own, but God Almighty has repeatedly disclosed to me that I am the Krishna - King of the Aryas - who was to appear in the latter days...” (TEOI, V4, P83)

and then there was this entire debate about Prophet Mohammad, of all places, in Quora.

Reminds of the time that I managed to wind up somebody on a mailing list when I said that given that the God that Jews, Christians and Muslims worship is the same (although some people quibble about it, see here and here), then Judaism, Christianity and Islam are all different sects. Not such a good idea.

anyway, it was quite interesting to read the Islamic links to Kalki...

Thursday, December 24

Fwd: Should vegans eat meat to be ethically consistent?

Kannu

This was an interesting argument from one of your oxford uni mates. Do you know this fellow?

I am conflicted about vegetarianism and non-vegetariansm. If you had asked me few years back, I would have been a strict non-veg, if you take my bacon away, there will be blood on the floor, and no pun intended. But I am starting to wonder now, from a medical perspective as well as an ethical perspective. And then there is the joke, I eat meat not because i love meat but because I hate animals. My work with the animal charity also is making me question non-vegetarianism. Finally, I go see the zoo's and feel really bad about the animals, specially after seeing them out in the wild, magnificent creatures and we pen them into tiny cages. Sad.

You may want to give this prize a shot..what do you think?

Love

Baba

Practical Ethics Ethics in the News

Should vegans eat meat to be ethically consistent? And other moral puzzles from the latest issue of the Journal of Practical Ethics

Dec 24th 2015, 05:32, by Brian D. EarpShould vegans eat meat to be ethically consistent? And other moral puzzles from the latest issue of the Journal of Practical Ethics

By Brian D. Earp (@briandavidearp)

The latest issue of The Journal of Practical Ethics has just been published online, and it includes several fascinating essays (see the abstracts below). In this blog post, I'd like to draw attention to one of them in particular, because it seemed to me to be especially creative and because it was written by an undergraduate student! The essay – "How Should Vegans Live?" – is by Oxford student Xavier Cohen. I had the pleasure of meeting Xavier several months ago when he presented an earlier draft of his essay at a lively competition in Oxford: he and several others were finalists for the Oxford Uehiro Prize in Practical Ethics, for which I was honored to serve as one of the judges.

In a nutshell, Xavier argues that ethical vegans – that is, vegans who refrain from eating animal products specifically because they wish to reduce harm to animals – may actually be undermining their own aims. This is because, he argues, many vegans are so strict about the lifestyle they adopt (and often advocate) that they end up alienating people who might otherwise be willing to make less-drastic changes to their behavior that would promote animal welfare overall. Moreover, by focusing too narrowly on the issue of directly refraining from consuming animal products, vegans may fail to realize how other actions they take may be indirectly harming animals, perhaps even to a greater degree.

Ecuador Is The World's First Country With A Public Digital Cash System

Did you notice the payments scanner in the taxis we took in Quito? Here's a bit more information on the system.

I was completely gobsmacked to be in a country which doesn't have its own currency that it controls. I know the euro is something like that but to live in a country which has willingly given up control of its currency means such a giant loss of sovereignty that I'm amazed. One of the reasons why I hate the euro. I as a citizen have no power over the currency is such a crazy situation. And then the irony that a leftist government (remember how all the guides were fulminating against the president?) having no control over its currency and being driven by the arch priest of right wingers, the USA. And the final indignity, the central bank building is now converted into a sodding numismatic museum. Tragic son tragic.

Remind me to tell you about blockchains sometime.

Love

Baba

Ecuador Is The World'sic First Country With A Public Digital Cash System

http://www.fastcoexist.com/3049536/ecuador-is-the-worlds-first-country-with-a-public-digital-cash-system

(via Instapaper)

The runaway success of mobile money products like M-Pesa, which first took off in Kenya, has inspired dozens of copycats around the world. Many countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America now have services allowing people to store and transfer money using their cellphones. But there's something different about Ecuador's new Sistema de Dinero Electrónico. It's being operated not by a private phone carrier or financial company, but Ecuador's left-leaning government.

M-Pesa-like products have been hailed for bringing millions of people into the formal financial system, enabling commerce between people in different locations, and cutting theft and tax avoidance. But Diego Martinez, an economist in Ecuador's central bank, says the government wanted its own service, because it thinks it can reduce the transaction costs that come with private offerings.

Wednesday, December 23

The girl with a book

Tuesday, December 22

slaughtering the commonly held shibboleths

I read this article today shown below. Its a great article son. Very very interesting. A small article but which really nails the commonly held tropes and shibboleths which are extant in the world today. Such a clear and articulate argument son. People do not really appreciate these basic truths. The links are very valuable as well. I have remarked on all these points generally other than perhaps the feminism angle, havent really worked or commented on it that much but very interesting son. Worth spending an hour to go through the links, you will find it very beneficial for your studies as well as arguments for politics and philosophy.

Love

Baba

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2015/12/labor_econ_vers.html

| My 13-year-old homeschooled sons just finished my labor economics class. I hope they take many more economics classes, but I'll be perfectly satisfied with their grasp of economics as long as they internalize what they learned this semester. Why? Because a good labor economics class contains everything you need to see through the central tenets of our society's secular religion. Labor economics stands against the world. Once you grasp its lessons, you can never again be a normal citizen. |

Friday, December 18

A List of Authors' Famous Last Words

I loved this list. And made me think kids, when I die, what do I want my last words to be?

My thought is, 'wheeee, my next life, here I come'

Fun times eh? It's the final adventure. The great unknown. Will be so great. I just hope I'm not going to be like Churchill and say, I'm bored of all this. Of course I'm not bored of all this. But that journey beyond death is fun.

Anyway. Happy reading.

I'm looking forward to the movie tonight with both of you.

Love

Baba

A List of Authors' Famous Last Words

http://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/a-list-of-authors-famous-last-words

(via Instapaper)

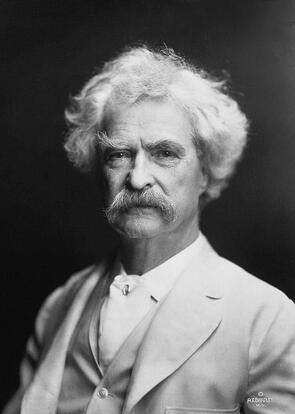

If you spend your entire life writing, it makes sense to make your last words count. Mark Twain recommended employing one's final breath in a deliberate, dignified message. Death is too important an occasion for improvisation or whimsy. Twain wrote, "There is hardly a case on record where a man came to his last moment unprepared and said a good thing — hardly a case where a man trusted to that last moment and did not make a solemn botch of it and go out of the world feeling absurd." After all, no author ought to die failing in the very thing he or she made a living perfecting. Below, there are numerous examples of writers' last words. Some, you'll find, are more poetic than others.

"I must go in, the fog is rising." —Emily Dickinson

Leave it to Dickinson to stay poetic in the most overwhelming of situations.

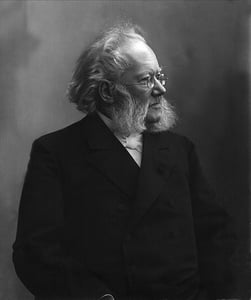

"On the contrary!" —Henrik Ibsen

Ibsen's comic response to his maid, who suggested the playwright's health was improving, endures for many of his fans.

"I want nothing but death." —Jane Austen

This was Austen's reply to her sister when asked what her wish was.

"It is most beautiful." —Elizabeth Barrett Browning

The Victorian poet's send-off is a cheery juxtaposition to Austen's.

"Moose...Indian" —Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau's last words were both nonsensical and fitting.

"Take away these pillows, I won't need them any longer." —Lewis Carroll

Carroll evidently knew his time was coming to an end, and left the world with both a trivial and dramatic declaration.

"I don't think two people could have been happier than we have been. V." —Virginia Woolf

These are the last sentences of Woolf's suicide note. She was addressing her husband, Leonard.

"God Bless Captain Vere!" —Herman Melville

The great American novelist spent his last moment partially living in his fiction. Captain Vere is a character in Billy Budd, which Melville worked on until his death.

"I am sorry to trouble you chaps. I don't know how you get along so fast with the traffic on the road these days." —Ian Fleming

When Fleming's body finally had its fill of scotch and cigars, the James Bond author apologized to the medics in his ambulance for the inconvenience he caused

"What's that? Does my face look strange?" —Robert Louis Stevenson

There are minor variations of Stevenson's final words (e.g. "Do I look strange?"). Either way, the Jekyll and Hyde author's last words were a response to the brain hemmorage that in only moments was to incapacitate and kill him.

"A certain butterfly is already on the wing." —Vladimir Nabokov

This is a fitting final line for the lepidoptderist Vladimir Nabokov. A master of self-publicizing, Nabokov likely did not leave these final words to chance.

"Dying men can do nothing easy." —Benjamin Franklin

The American Renaissance man said this to his daughter, who prompted him to lay differently so he could breathe less laboriously.

"Does nobody understand?" —James Joyce

These last words are fitting for a true mischief-man of literature. Writer of Finnegans Wake, Joyce was an experimenter who worked and tested the very limits of language. His final lines also express the thoughts of many English teachers who have ever taught one of his books.

"Goodnight, my kitten." —Ernest Hemingway

These words were said to the author's wife, right before he was to take his life at the age of 61.

"I'm bored with it all." —Winston Churchill

In true Churchillian fashion the former Prime Minister let death know it had his permission to take him.

"On the ground" —Charles Dickens

Dickens' final words were said as he experienced a stroke at home. It was a reply to his sister-in-law Georgina who recommended lying down.

"Well, I've had a happy life" —William Hazlitt

These last words are rather sanguine for a man who wrote an essay called "On the Pleasure of Hating."

"I don't think they even heard me" —Yukio Mishima

Mishima addressed a crowd of soldiers in Japan, encouraging them to overthrow the government and restore the power of the emperor. He died soon after from a gruesomely-executed seppuku.

"All right then, I'll say it: Dante makes me sick" —Lope de Vega

The Renaissance playwright was able to get this literary grievance off of his chest before leaving our world.

"Warry, shift!" —Walt Whitman

The poet's last words to a nurse are not likely to be counted among his best.

"This is the fight of day and night. I see black light." —Victor Hugo

The Notre Dame de Paris author's poetic last words echo Goethe's "Oh light!"

"Good bye. If we meet…" —Mark Twain

Addressed to his daughter Clara, Mark Twain's final words were more about extending love than preserving his reputation for cleverness.

"I believe we shall adjourn this meeting to another place." —Adam Smith

The economist said this before the invisible hand of mortality came for its prize.

"Go on, get out. Last words are for fools who haven't said enough." —Karl Marx

Marx said this to his housekeeper who wondered with what style the thinker was going to depart this world.

Which are your favorites? Did we miss any authors' famous last words? Let us know in the comments below!

Reader, specializing in Twentieth Century and contemporary fiction. Committed to spreading an infectious passion for literature, language, and stories.

Thursday, December 17

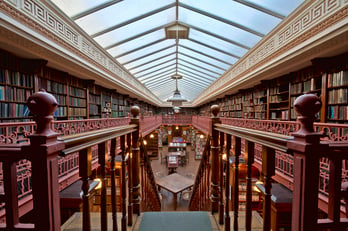

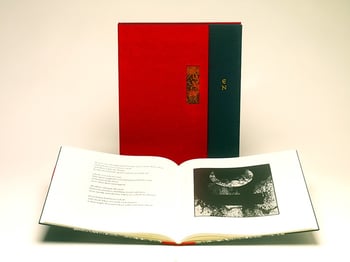

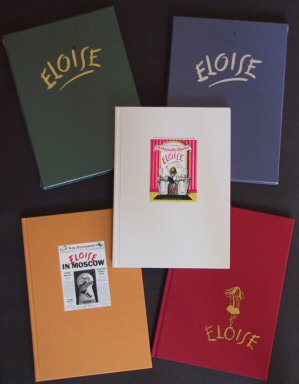

A Brief Guide to Starting a Rare Book Collection

There's something about gathering rare books. I like collecting old books on history and not that fussed about the first editions. It's more to do with the age and the topic. And I hope they will be worth few bob when I die and then you can decide to keep them or sell them off.

It's just such a lovely feeling when you start to explore the rare and antiquarian book. You imagine the various hands it has passed through. The people who have bought it. The people who stocked it. The people who browsed it but didn't buy. The people who stacked it. The people who dusted them. The people who read it. The people who had the book read aloud to them. The people who saw it. Books passing through multiple generations of a family. The weight of tradition and love and emotions and feelings. It's just such a lovely feeling. And then I stand in front of our bookshelf and say, hello ladies. Who shall I date tonight :)

I'm so happy that both of you are interested in books :) love it.

Love you

Baba

A Brief Guide to Starting a Rare Book Collection

http://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/a-brief-guide-to-starting-a-rare-book-collection

(via Instapaper)

Collecting rare books is at once a hobby, a passion, and an art form. The process is filled with nuances, and there are perhaps as many ways to go about forming a collection as there are collectors. However, some universal truths are present in the book collecting world. Here, we've compiled a brief guide to help you along your collecting ways. Whether you're just starting out or if you have been at it awhile, we hope what follows is helpful. And we hope you'll share with us in the comments below what you've learned and the skills you've honed through your own personal collecting journey.

What is a Rare Book Collection?

Before we begin, it is only fair to note that there is a difference between a book collection and a personal library. Both are good and beautiful things, but they are different. Many of us have personal libraries in our homes: all those used books purchased for college courses, the stack of children's books peppering the bottom shelf, how-to compendiums for the first-time homeowner, etc. In short, a personal library includes books we've acquired in numerous ways, and there's often not a clear theme present. It is what it is — a library with many topics in its arsenal. A collection, on the other hand, is a focused attempt to amass a specific type of book, usually of a certain quality.

So, now that we've identified the difference between a personal library and a book collection, we must also recognize that there are different types of book collections.

Collecting Around a Central Topic

Many collectors choose a topic of interest to them and base their collection on it. We've heard of collectors who focus on a particular sport, an event in history, a part of the country, etc.

Keep in mind when you're deciding on a topic-based collection that some topics are too broad to allow for a thorough and full accumulation of texts. World War II, for instance, may be of particular interest to you. Yet, collecting books on WWII without a more refined search criteria could leave you floundering. Instead, perhaps it would be better to focus on a particular author in the WWII era, or on a particular battle, or books out of a specific region written during or about the war.

Collecting Around a Specific Author

As we mentioned above, another way to go about focusing one's collection is to pick an inspiring author and go after his or her works. We've written about the challenge and reward of Rudyard Kipling, for example. He is just one of many authors who provide an outstanding outlet for book collecting enthusiasts. Think about who speaks to you through their work, and start there.

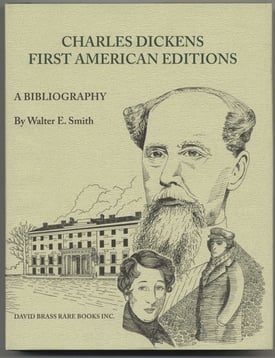

Keep in mind that collecting as a 'completist,' that is, aiming to collect every item from a single author (all of the works of Charles Dickens, for example), is an incredibly ambitious, expensive, and in some case, unfeasible endeavor. Rather than getting overwhelmed by the daunting nature of such a task, we'd recommend choosing a tighter focus within the category of your author of choice and going from there.

If you're not sure where to begin your collection, you can look to lists of award-winning books or authors (Pulitzer Prize winners, Nobel Prize winners, etc.) for some inspiration.

Collecting Books Based on Looks

Other collectors focus on aesthetic appeal when they are acquiring books. Some prefer to compile a collection of leather bound books. Franklin Library editions, for instance, include beautiful classic, leather-bound books. In recent years, many have been signed by the author. They make for very aesthetically appealing collectibles.

Another option for collecting books based on looks is to work to accumulate fine press editions. Fine press books often have truly unique stories behind their creation, making them not only items that look pretty on the shelf, but also inspirational pieces of craftsmanship. A fine press book is often printed by a small press in close collaboration with the author, thus limited quantities are usually available. This makes for a supremely interesting and usually incredibly visually appealing addition to one's collection.

A Note About Dust Jackets

Speaking of aesthetics, keep the importance of dust jackets in mind as you begin your collection. Finding books in their original dust jackets is a challenging and fascinating venture. Early dust jackets (pre-20th century) are incredibly unique and a major bonus to one's collection. For modern first editions (most of the 20th century), acquiring a book with its original dust jacket in fine or near-fine condition will mean the difference between an incredibly valuable collectible and one that doesn't hold much weight. Many early dust jackets were destroyed by the original owners who wanted to display the actual bindings of the books, which now means that dust jackets still in existence and in good shape are rare and valuable finds.

Narrow Your Focus

The key to any book collection is a specific focus. One must outline her budget, her goals, and create a reasonable plan of attack. A narrower focus allows you to zero in on what's important and build a truly rich collection of works that matter to you. That way, you're not wasting funds and shelf space on books that don't really suit the needs and purpose of your collection.

Once you've decided on a type of collection (and you can most certainly have more than one!), it's time to start figuring out what kinds of books you'll be looking to add to your shelves.

Collecting Basics

It's important to understand the terms of the trade as you sift through the many pools of rare books. You can look for collectible books at library book sales, rare book fairs, auctions, antiquarian book stores, online, or in your grandmother's attic. Truly, the opportunities and avenues to starting a rare book collection (and building it!) are endless. Whatever route you choose, though, it's helpful to know what different terms mean when you're presented with a copy that may be of interest.

We've compiled several glossaries of rare book terms to help you along.

In many cases, serious book collectors are after first editions. As you are getting started, keep in mind that first edition/first impression (or first edition/first printing) is the real gem, whereas a first edition and a subsequent impression often wouldn't be considered as appealing. It can still be valuable and a worthwhile purchase, but in most cases, you shouldn't be paying as much for it.

An essential tool to help you along your collecting way is a bibliography. Bibliographies exist for different authors or different collecting categories, and they chronicle imperative information regarding first edition 'points' so that a collector can identify and distinguish first impressions (first printings) from later impressions.

Other Collecting Considerations

A signed copy of a text you've been coveting makes a brilliant addition to one's collection, as does a limited edition. Limited editions are printed, much like the title suggests, in limited quantities. Usually, they will be numbered, and once they are gone, they are gone.

A limited edition book is different than say, a deluxe edition. Though they both may include extra features like illustrations or an author's note, a deluxe edition is not necessarily printed in limited quantities, which again, affects its value.

Once you've started to amass a collection, it can be exciting to try to add ephemera and other artifacts that are associated with your topic, author, or collection style. Playbills, advertisements, newspaper articles, letters, and a whole host of other options are often some of the most fun elements of any given collection.

Why Should You Collect?

Individuals collect rare books for a variety of reasons. As we just mentioned, some are after it for the fun — the thrill of the chase and the satisfaction of nabbing a pristine copy. Book collectors will tell you theirs is one of the most enjoyable and rewarding hobbies. What's better than a collection of books to serve as a conversation starter when guests arrive?

Beyond that, though, a book collection is wonderful for posterity. Many collectors collect with future generations in mind. Whether their aim is to pass down their collection to family members or bequeath it to a community organization, book collectors often use the acquisition of their rare books to serve the greater good.

Caring for Your Collection

Once you've started to compile a book collection, it's important to take good care of it! You've worked hard, and you don't want your collection to lose any of its value because it has been stored improperly. Remember when you're choosing where to house your collection that storing books in a sunny library can lead to sunning. Likewise, exposure to humidity can lead to foxing. Many book collectors choose to store their dust jackets in protectors separate from the books themselves. That way, they get the benefit of looking at the book binding while also having access to the valuable dust jackets (and knowing that they are in a safe spot!). Keeping in mind that a collection is often prized for the sake of posterity, it makes sense to take good care of one's books not just so they maintain their material value, but also so they can be enjoyed for generations to come.

Key Takeaways

In conclusion, our recommendations are to start small, with a manageable focus. Learn the terms of the book collectors world so you know what to look for, and what you're paying for. Make sure you care for your books. And most importantly, enjoy the process and the fruits of your labor!

The Container Ship Tourism Industry

Kids

I read this article and was instantly captivated. What a great idea no? Jumping into a container ship and just going around the world to see parts which the normal tourist doesn't see. And then the solitude and silence. The sea is an amazing place kids. Specially at night. While we were on the Nemo, that's what I loved doing, going and sitting alone in the bow or in the poop deck or on the top deck.

This kind of travel isn't for everybody. I've noticed this with so many people kids. They need other people to be entertained. Not many people have the capacity to entertain themselves. What I'm happy about is that you too show the signs that you can entertain yourself. If nothing else, learn to laugh at yourself kids. As the old saying goes, learn to laugh at yourself, you will never cease to be entertained.

I'm going to try to find more about this type of travel. I like the idea of going around the Barents Sea or the route to Murmansk. That trip is on my bucket list. I think I've mentioned this to you before but one of the few books I cried reading was Alastair Maclean's HMS Ulysses, the story of a light cruiser (the same type like HMS Belfast which is moored on the Thames. When the captain died.

That Arctic convoy duty was some of the most horrendous duties ever made. Tremendous cold. Fear. Hunger. Sleep deprivation. Dripping cold steel. I'm sure it will not be like that when I go but at least I can follow in the footsteps. The same type of voyage was done by the chap who wrote about the Panama hat. He went on a cargo ship as well from guyamil (where we stopped over on the way to Galapagos) and went up to Panama and the west coast of USA. Do read that book if you can.

So that's the first one. The second trip that would be good would be around the Mediterranean Sea. Stopping at the smaller ports. Now that would be fascinating. Stepping in the footsteps (can I say that for a sea voyage?) of the Phoenicians and Carthignans and the Venetians and and and. We can do either trip in 2 weeks. The longer one will be the African port although that will not be fun. Another interesting one will be to try to replicate the route taken by Prince Henry's navigators in Portugal , starts from Lisbon and down the west coast of Africa, around the Cape of good hope and then up the east coast (searching for the mythical Christian Kingdom of Prestor John) and then cutting across to India via Yemen and Oman. Far too dangerous of course but it's fun to dream eh?

I know Kannu is thinking, baba is doing a chimneys post again! :)

Love you two, sorry this week has been a bit of nightmare at work and will keep on till end the month at least. Usual stuff this time of the year with the annual budgeting cycle. I'm forcing everybody to think about 2016 while everybody is busy about 2015. Some people can't plan worth spit but that's my job, to make sure people look months and years in front so that they have the resources when they need it. You dig a well now, not when your house is on fire next year.

Fun times.

Love

Baba

C

The Container Ship Tourism Industry

http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-container-ship-tourism-industry

(via Instapaper)

Robert Rieffel was strolling with his wife and friends along River Street in Savannah, Georgia, a touristy corridor filled with trinket shops and restaurants, when he suddenly heard “this big brooooooooooo,” he says, imitating the sound of a ship’s horn. An enormous cargo ship was sailing up the river, one of many that travel international routes delivering everything from kitty litter to cars to clothes in massive stacks of metal shipping containers. Rieffel was captivated.

Wednesday, December 16

How the Inca Empire Engineered a Road Across Some of the World's Most Extreme Terrain

Kids

You will recognise this from our trip to Ecuador. We drove on this road when we went up to the Amazonia hakuna matata resort. And you'll also recognise the language that this article mentions. Kannu, remember the people we had during the white water rafting time? The guide, his wife and others? They spoke Quechua.

This idea of having gods on or alongside roads is a very long tradition. When I was recently in india, every pass and mountain road had Hindu and Muslim shrines next to it. Remember where we stopped to have lunch on the way to the resort? That had a Madonna shrine as well. It's for people to pray for good luck and fortune in the journey and return.

Fascinating how roads become holy no?

Love

Baba

How the Inca Empire Engineered a Road Across Some of the World's Most Extreme Terrain

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-inca-empire-engineered-road-would-endure-centuries-180955709/

(via Instapaper)

Every June, after the rainy season ends in the grassy highlands of southern Peru, the residents of four villages near Huinchiri, at more than 12,000 feet in altitude, come together for a three-day festival. Men, women and children have already spent days in busy preparation: They've gathered bushels of long grasses, which they've then soaked, pounded, and dried in the sun. These tough fibers have been twisted and braided into narrow cords, which in turn have been woven together to form six heavy cables, each the circumference of a man's thigh and more than 100 feet long.

Dozens of men heave the long cables over their shoulders and carry them single file to the edge of a deep, rocky canyon. About a hundred feet below flows the Apurímac River. Village elders murmur blessings to Mother Earth and Mother Water, then make ritual offerings by burning coca leaves and sacrificing guinea pigs and sheep.

Shortly after, the villagers set to work linking one side of the canyon to the other. Relying on a bridge they built the same way a year earlier—now sagging from use—they stretch out four new cables, lashing each one to rocks on either side, to form the base of the new 100-foot long bridge. After testing them for strength and tautness, they fasten the remaining two cables above the others to serve as handrails. Villagers lay down sticks and woven grass mats to stabilize, pave and cushion the structure. Webs of dried fiber are quickly woven, joining the handrails to the base. The old bridge is cut; it falls gently into the water.

At the end of the third day, the new hanging bridge is complete. The leaders of each of the four communities, two from either side of the canyon, walk toward one another and meet in the middle. "Tukuushis!" they exclaim. "We've finished!"

And so it has gone for centuries. The indigenous Quechua communities, descendants of the ancient Inca, have been building and rebuilding this twisted-rope bridge, or Q'eswachaka, in the same way for more than 500 years. It's a legacy and living link to an ancient past—a bridge not only capable of bearing some 5,000 pounds but also empowered by profound spiritual strength.

To the Quechua, the bridge is linked to earth and water, both of which are connected to the heavens. Water comes from the sky; the earth distributes it. In their incantations, the elders ask the earth to support the bridge and the water to accept its presence. The rope itself is endowed with powerful symbolism: Legend has it that in ancient times the supreme Inca ruler sent out ropes from his capital in Cusco, and they united all under a peaceful and prosperous reign.

The bridge, says Ramiro Matos, physically and spiritually "embraces one side and the other side." A Peruvian of Quechua descent, Matos is an expert on the famed Inca Road, of which this Q'eswachaka makes up just one tiny part. He's been studying it since the 1980s and has published several books on the Inca.

For the past seven years, Matos and his colleagues have traveled throughout the six South American countries where the road runs, compiling an unprecedented ethnography and oral history. Their detailed interviews with more than 50 indigenous people form the core of a major new exhibition, "The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire," at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of the American Indian.

"This show is different from a strict archaeological exhibition," Matos says. "It's all about using a contemporary, living culture to understand the past." Featured front and center, the people of the Inca Road serve as mediators of their own identity. And their living culture makes it clear that "the Inca Road is a living road," Matos says. "It has energy, a spirit and a people."

Matos is the ideal guide to steer such a complex project. For the past 50 years, he has moved gracefully between worlds—past and present, universities and villages, museums and archaeological sites, South and North America, and English and non-English speakers. "I can connect the contemporary, present Quechua people with their past," he says.

Numerous museum exhibitions have highlighted Inca wonders, but none to date have focused so ambitiously on the road itself, perhaps because of the political, logistical and conceptual complexities. "Inca gold is easy to describe and display," Matos explains. Such dazzling objects scarcely need an introduction. "But this is a road," he continues. "The road is the protagonist, the actor. How do we show that?"

The sacred importance of this thoroughfare makes the task daunting. When, more than a hundred years ago, the American explorer Hiram Bingham III came across part of the Inca Road leading to the fabled 15th-century site of Machu Picchu, he saw only the remains of an overgrown physical highway, a rudimentary means of transit. Certainly most roads, whether ancient or modern, exist for the prosaic purpose of aiding commerce, conducting wars, or enabling people to travel to work. We might get our kicks on Route 66 or gasp while rounding the curves on Italy's Amalfi Coast—but for the most part, when we hit the road, we're not deriving spiritual strength from the highway itself. We're just aiming to get somewhere efficiently.

Not so the Inca Road. "This roadway has a spirit," Matos says, "while other roads are empty." Bolivian Walter Alvarez, a descendant of the Inca, told Matos that the road is alive. "It protects us," he said. "Passing along the way of our ancestors, we are protected by the Pachamama [Mother Earth]. The Pachamama is life energy, and wisdom." To this day, Alvarez said, traditional healers make a point of traveling the road on foot. To ride in a vehicle would be inconceivable: The road itself is the source from which the healers absorb their special energy.

"Walking the Inca Trail, we are never tired," Quechua leader Pedro Sulca explained to Matos in 2009. "The llamas and donkeys that walk the Inca Trail never get tired … because the old path has the blessings of the Inca."

It has other powers too: "The Inca Trail shortens distances," said Porfirio Ninahuaman, a Quechua from near the Andean city of Cerro de Pasco in Peru. "The modern road makes them farther." Matos knows of Bolivian healers who hike the road from Bolivia to Peru's central highlands, a distance of some 500 miles, in less than two weeks.

"They say our Inka [the Inca king] had the power of the sun, who commanded on earth and all obeyed—people, animals, even rocks and stones," said Nazario Turpo, an indigenous Quechua living near Cusco. "One day, the Inka, with his golden sling, ordered rocks and pebbles to leave his place, to move in an orderly manner, form walls, and open the great road for the Inca Empire… So was created the Capac Ñan."

This monumental achievement, this vast ancient highway—known to the Inca, and today in Quechua, as Capac Ñan, commonly translated as the Royal Road but literally as "Road of the Lord"—was the glue that held together the vast Inca Empire, supporting both its expansion and its successful integration into a range of cultures. It was paved with blocks of stone, reinforced with retaining walls, dug into rock faces, and linked by as many as 200 bridges, like the one at Huinchiri, made of woven-grass rope, swaying high above churning rivers. The Inca engineers cut through some of the most diverse and extreme terrain in the world, spanning rain forests, deserts and high mountains.

At its early 16th-century peak, the Inca Empire included between eight million and twelve million people and extended from modern-day Colombia down to Chile and Argentina via Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru. The Capac Ñan linked Cusco, the Inca capital and center of its universe, with the rest of the realm, its main route and tributaries radiating in all directions. The largest empire in its day, it also ranked as among the most sophisticated, incorporating a diverse array of chiefdoms, kingdoms and tribes. Unlike other great empires, it used no currency. A powerful army and extraordinary central bureaucracy administered business and ensured that everyone worked—in agriculture until the harvest, and doing public works thereafter. Labor—including work on this great road—was the tax Inca subjects paid. Inca engineers planned and built the road without benefit of wheeled devices, draft animals, a written language, or even metal tools.

The last map of the Inca Road, considered the base map until now, was completed more than three decades ago, in 1984. It shows the road running for 14,378 miles. But the remapping conducted by Matos and an international group of scholars revealed that it actually stretched for nearly 25,000 miles. The new map was completed by Smithsonian cartographers for inclusion in the exhibition. Partly as a result of this work, the Inca Road became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2014.

Before Matos became professionally interested in the road, it was simply a part of his daily life. Born in 1937 in the village of Huancavelica, at an altitude of some 12,000 feet in Peru's central highlands, Matos grew up speaking Quechua; his family used the road to travel back and forth to the nearest town, some three hours away. "It was my first experience of walking on the Inca Road," he says, though he didn't realize it then, simply referring to it as the "Horse Road." No cars came to Huancavelica until the 1970s. Today his old village is barely recognizable. "There were 300 people then. It's cosmopolitan now."

As a student in the 1950s at Lima's National University of San Marcos, Matos diverged from his path into the legal profession when he realized that he enjoyed history classes far more than studying law. A professor suggested archaeology. He never looked back, going on to become a noted archaeologist, excavating and restoring ancient Andean sites, and a foremost anthropologist, pioneering the use of current native knowledge to understand his people's past. Along the way, he has become instrumental in creating local museums that safeguard and interpret pre-Inca objects and structures.

Since Matos first came to the United States in 1976, he has held visiting professorships at three American universities, as well as ones in Copenhagen, Tokyo and Bonn. That's in addition to previous professorial appointments at two Peruvian universities. In Washington, D.C., where he's lived and worked since 1996, he still embraces his Andean roots, taking part in festivals and other activities with fellow Quechua immigrants. "Speaking Quechua is part of my legacy," he says.

Among the six million Quechua speakers in South America today, many of the old ways remain. "People live in the same houses, the same places, and use the same roads as in the Inca time," Matos says. "They're planting the same plants. Their beliefs are still strong."

But in some cases, the indigenous people Matos and his team interviewed represent the last living link to long-ago days. Seven years ago, Matos and his team interviewed 92-year-old Demetrio Roca, who recalled a 25-mile walk in 1925 with his mother from their village to Cusco, where she was a vendor in the central plaza. They were granted entrance to the sacred city only after they had prayed and engaged in a ritual purification. Roca wept as he spoke of new construction wiping out his community's last Inca sacred place—destroyed, as it happened, for road expansion.

Nowadays, about 500 communities in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and northwestern Argentina rely on what remains of the road, much of it overgrown or destroyed by earthquakes or landslides. In isolated areas, it remains "the only road for their interactions," Matos says. While they use it to go to market, it's always been more than just a means of transport. "For them," Matos says, "it's Mother Earth, a companion." And so they make offerings at sacred sites along the route, praying for safe travels and a speedy return, just as they've done for hundreds of years.

That compression of time and space is very much in keeping with the spirit of the museum exhibition, linking past and present—and with the Quechua worldview. Quechua speakers, Matos says, use the same word, pacha, to mean both time and space. "No space without time, no time without space," he says. "It's very sophisticated."

The Quechua have persevered over the years in spite of severe political and environmental threats, including persecution by Shining Path Maoist guerrillas and terrorists in the 1980s. Nowadays the threats to indigenous people come from water scarcity—potentially devastating to agricultural communities—and the environmental effects of exploitation of natural resources, including copper, lead and gold, in the regions they call home.

"To preserve their traditional culture, [the Quechua] need to preserve the environment, especially from water and mining threats," Matos emphasizes. But education needs to be improved too. "There are schools everywhere," he says, "but there is no strong pre-Hispanic history. Native communities are not strongly connected with their past. In Cusco, it's still strong. In other places, no."

Still, he says, there is greater pride than ever among the Quechua, partly the benefit of vigorous tourism. (Some 8,000 people flocked to Huinchiri to watch the bridge-building ceremony in June last year.) "Now people are feeling proud to speak Quechua," Matos says. "People are feeling very proud to be descendants of the Inca." Matos hopes the Inca Road exhibition will help inspire greater commitment to preserving and understanding his people's past. "Now," he says, "is the crucial moment."

This story is from the new travel quarterly, Smithsonian Journeys, which will arrive on newstands July 14.

"The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire" is on view at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. through June 1, 2018."

Ferguson’s Formula

Kannu

As you read this, you'll find that there is no formula. As in something with constants and variables and coefficients and functions. No sir. This is not an equation or a formula. Big danger in assuming that you always have a formula. Pick up the formula and apply and in 2 days you'll be successful as Ferguson. It doesn't work like this son.

Yes these guidelines work and make sense but the conditions have to come together. Take for example the point about observation son. I need to have a team who do the work so that I can observe. What if I don't have sufficient people? Then I have to do work!

But some good advice son. Invest in the young. Keep changing and be flexible.

Then again remember even greats like him have problems. Think of his succession planning. Didn't quite work out did it?

So beware of trite advice son. Hard work. Flexibility all these help.

Can't wait to see you tonight and squish you. I missed you and plus I need to hug you to congratulate you on your internship.

Love

Baba

Ferguson's Formula

https://hbr.org/2013/10/fergusons-formula

(via Instapaper)

Reprint: R1310G

When Alex Ferguson took over as manager of the English football team Manchester United, the club was in dire straits: It hadn't won a league title in nearly 20 years and faced a very real threat of being relegated to a lower division. In 26 seasons under Ferguson, United won 38 domestic and international trophies—giving him nearly twice as many as any other English club manager—and became one of the valuable franchises in sports.

In 2012, during Ferguson's final season before retiring, Harvard Business School professor Anita Elberse had the unique opportunity to observe Ferguson's management style in a series of visits and in-depth interviews. In this collaborative explication, she details eight parts of Ferguson's "formula" as she observed them and gives the manager his say. The lessons described range from the necessity of maintaining control over high-performing team members to the importance of observation and the inevitability of change. The approach that brought Ferguson's team such success and staying power is applicable well beyond football—to business and to life.

Some call him the greatest coach in history. Before retiring in May 2013, Sir Alex Ferguson spent 26 seasons as the manager of Manchester United, the English football (soccer) club that ranks among the most successful and valuable franchises in sports. During that time the club won 13 English league titles along with 25 other domestic and international trophies—giving him an overall haul nearly double that of the next-most-successful English club manager. And Ferguson was far more than a coach. He played a central role in the United organization, managing not just the first team but the entire club. "Steve Jobs was Apple; Sir Alex Ferguson is Manchester United," says the club's former chief executive David Gill.

In 2012 Harvard Business School professor Anita Elberse had a unique opportunity to examine Ferguson's management approach and developed an HBS case study around it. Now she and Ferguson have collaborated on an analysis of his enormously successful methods.

Anita Elberse: Success and staying power like Sir Alex Ferguson's demand study—and not just by football fans. How did he do it? Can one identify habits that enabled his success and principles that guided it? During what turned out to be his final season in charge, my former student Tom Dye and I conducted a series of in-depth interviews with Ferguson about his leadership methods and watched him in action at United's training ground and at its famed stadium, Old Trafford, where a nine-foot bronze statue of the former manager now looms outside. We spoke with many of the people Ferguson worked with, from David Gill to the club's assistant coaches, kit manager, and players. And we observed Ferguson during numerous short meetings and conversations with players and staff members in the hallways, in the cafeteria, on the training pitch, and wherever else the opportunity arose. Ferguson later came to HBS to see the ensuing case study taught, provide his views, and answer students' questions, resulting in standing-room-only conditions in my classroom and a highly captivating exchange.

Ferguson and I discussed eight leadership lessons that capture crucial elements of his approach. Although I've tried not to push the angle too hard, many of them can certainly be applied more broadly, to business and to life. In the article that follows, I describe each lesson as I observed it, and then give Ferguson his say.

1. Start with the Foundation

Upon his arrival at Manchester, in 1986, Ferguson set about creating a structure for the long term by modernizing United's youth program. He established two "centers of excellence" for promising players as young as nine and recruited a number of scouts, urging them to bring him the top young talent. The best-known of his early signings was David Beckham. The most important was probably Ryan Giggs, whom Ferguson noticed as a skinny 13-year-old in 1986 and who went on to become the most decorated British footballer of all time. At 39, Giggs is still a United regular. The longtime stars Paul Scholes and Gary Neville were also among Ferguson's early youth program investments. Together with Giggs and Beckham, they formed the core of the great United teams of the late 1990s and early 2000s, which Ferguson credits with shaping the club's modern identity.

It was a big bet on young talent, and at a time when the prevailing wisdom was, as one respected television commentator put it, "You can't win anything with kids." Ferguson approached the process systematically. He talks about the difference between building a team, which is what most managers concentrate on, and building a club.

Sir Alex Ferguson: From the moment I got to Manchester United, I thought of only one thing: building a football club. I wanted to build right from the bottom. That was in order to create fluency and a continuity of supply to the first team. With this approach, the players all grow up together, producing a bond that, in turn, creates a spirit.

When I arrived, only one player on the first team was under 24. Can you imagine that, for a club like Manchester United? I knew that a focus on youth would fit the club's history, and my earlier coaching experience told me that winning with young players could be done and that I was good at working with them. So I had the confidence and conviction that if United was going to mean anything again, rebuilding the youth structure was crucial. You could say it was brave, but fortune favors the brave.

The first thought of 99% of newly appointed managers is to make sure they win—to survive. So they bring experienced players in. That's simply because we're in a results-driven industry. At some clubs, you need only to lose three games in a row, and you're fired. In today's football world, with a new breed of directors and owners, I am not sure any club would have the patience to wait for a manager to build a team over a four-year period.

Winning a game is only a short-term gain—you can lose the next game. Building a club brings stability and consistency. You don't ever want to take your eyes off the first team, but our youth development efforts ended up leading to our many successes in the 1990s and early 2000s. The young players really became the spirit of the club.

I always take great pride in seeing younger players develop. The job of a manager, like that of a teacher, is to inspire people to be better. Give them better technical skills, make them winners, make them better people, and they can go anywhere in life. When you give young people a chance, you not only create a longer life span for the team, you also create loyalty. They will always remember that you were the manager who gave them their first opportunity. Once they know you are batting for them, they will accept your way. You're really fostering a sense of family. If you give young people your attention and an opportunity to succeed, it is amazing how much they will surprise you.

2. Dare to Rebuild Your Team

Even in times of great success, Ferguson worked to rebuild his team. He is credited with assembling five distinct league-winning squads during his time at the club and continuing to win trophies all the while. His decisions were driven by a keen sense of where his team stood in the cycle of rebuilding and by a similarly keen sense of players' life cycles—how much value the players were bringing to the team at any point in time. Managing the talent development process inevitably involved cutting players, including loyal veterans to whom Ferguson had a personal attachment. "He's never really looking at this moment, he's always looking into the future," Ryan Giggs told us. "Knowing what needs strengthening and what needs refreshing—he's got that knack."

Our analysis of a decade's worth of player transfer data revealed Ferguson to be a uniquely effective "portfolio manager" of talent. He is strategic, rational, and systematic. In the past decade, during which Manchester United won the English league five times, the club spent less on incoming transfers than its rivals Chelsea, Manchester City, and Liverpool did. One reason was a continued commitment to young players: Those under 25 constituted a far higher share of United's incoming transfers than of its competitors'. And because United was willing to sell players who still had good years ahead of them, it made more money from outgoing transfers than most of its rivals did—so the betting on promising talent could continue. Many of those bets were made on very young players on the cusp of superstardom. (Ferguson did occasionally shell out top money for established superstars, such as the Dutch striker Robin van Persie, bought for $35 million at the start of the 2012–2013 season, when he was 29.) Young players were given the time and conditions to succeed, most older players were sold to other teams while they were still valuable properties, and a few top veterans were kept around to lend continuity and carry the culture of the club forward.

Ferguson: We identified three levels of players: those 30 and older, those roughly 23 to 30, and the younger ones coming in. The idea was that the younger players were developing and would meet the standards that the older ones had set. Although I was always trying to disprove it, I believe that the cycle of a successful team lasts maybe four years, and then some change is needed. So we tried to visualize the team three or four years ahead and make decisions accordingly. Because I was at United for such a long time, I could afford to plan ahead—no one expected me to go anywhere. I was very fortunate in that respect.

Analyzing player transfer data reveals Ferguson to be a uniquely effective "portfolio manager" of talent. He is strategic, rational, and systematic.

The goal was to evolve gradually, moving older players out and younger players in. It was mainly about two things: First, who did we have coming through and where did we see them in three years' time, and second, were there signs that existing players were getting older? Some players can go on for a long time, like Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes, and Rio Ferdinand, but age matters. The hardest thing is to let go of a player who has been a great guy—but all the evidence is on the field. If you see the change, the deterioration, you have to ask yourself what things are going to be like two years ahead.

3. Set High Standards—and Hold Everyone to Them

Ferguson speaks passionately about wanting to instill values in his players. More than giving them technical skills, he wanted to inspire them to strive to do better and to never give up—in other words, to make them winners.

His intense desire to win stemmed in part from his own experiences as a player. After success at several small Scottish clubs, he signed with a top club, Rangers—the team he had supported as a boy—but soon fell out of favor with the new manager. He left Rangers three years later with only a Scottish Cup Final runner-up's medal to show for his time there. "The adversity gave me a sense of determination that has shaped my life," he told us. "I made up my mind that I would never give in."

Ferguson looked for the same attitude in his players. He recruited what he calls "bad losers" and demanded that they work extremely hard. Over the years this attitude became contagious—players didn't accept teammates' not giving it their all. The biggest stars were no exception.

Ferguson: Everything we did was about maintaining the standards we had set as a football club—this applied to all my team building and all my team preparation, motivational talks, and tactical talks. For example, we never allowed a bad training session. What you see in training manifests itself on the game field. So every training session was about quality. We didn't allow a lack of focus. It was about intensity, concentration, speed—a high level of performance. That, we hoped, made our players improve with each session.

I had to lift players' expectations. They should never give in. I said that to them all the time: "If you give in once, you'll give in twice." And the work ethic and energy I had seemed to spread throughout the club. I used to be the first to arrive in the morning. In my later years, a lot of my staff members would already be there when I got in at 7 AM. I think they understood why I came in early—they knew there was a job to be done. There was a feeling that "if he can do it, then I can do it."

I constantly told my squad that working hard all your life is a talent. But I expected even more from the star players. I expected them to work even harder. I said, "You've got to show that you are the top players." And they did. That's why they are star players—they are prepared to work harder. Superstars with egos are not the problem some people may think. They need to be winners, because that massages their egos, so they will do what it takes to win. I used to see [Cristiano] Ronaldo [one of the world's top forwards, who now plays for Real Madrid], Beckham, Giggs, Scholes, and others out there practicing for hours. I'd have to chase them in. I'd be banging on the window saying, "We've got a game on Saturday." But they wanted the time to practice. They realized that being a Manchester United player is not an easy job.

4. Never, Ever Cede Control

"You can't ever lose control—not when you are dealing with 30 top professionals who are all millionaires," Ferguson told us. "And if any players want to take me on, to challenge my authority and control, I deal with them." An important part of maintaining high standards across the board was Ferguson's willingness to respond forcefully when players violated those standards. If they got into trouble, they were fined. And if they stepped out of line in a way that could undermine the team's performance, Ferguson let them go. In 2005, when longtime captain Roy Keane publicly criticized his teammates, his contract was terminated. The following year, when United's leading scorer at the time, Ruud van Nistelrooy, became openly disgruntled over several benchings, he was promptly sold to Real Madrid.

Responding forcefully is only part of the story here. Responding quickly, before situations get out of hand, may be equally important to maintaining control.

Ferguson: If the day came that the manager of Manchester United was controlled by the players—in other words, if the players decided how the training should be, what days they should have off, what the discipline should be, and what the tactics should be—then Manchester United would not be the Manchester United we know. Before I came to United, I told myself I wasn't going to allow anyone to be stronger than I was. Your personality has to be bigger than theirs. That is vital.

There are occasions when you have to ask yourself whether certain players are affecting the dressing-room atmosphere, the performance of the team, and your control of the players and staff. If they are, you have to cut the cord. There is absolutely no other way. It doesn't matter if the person is the best player in the world. The long-term view of the club is more important than any individual, and the manager has to be the most important one in the club.

Some English clubs have changed managers so many times that it creates power for the players in the dressing room. That is very dangerous. If the coach has no control, he will not last. You have to achieve a position of comprehensive control. Players must recognize that as the manager, you have the status to control events. You can complicate your life in many ways by asking, "Oh, I wonder if the players like me?" If I did my job well, the players would respect me, and that's all you need.

I tended to act quickly when I saw a player become a negative influence. Some might say I acted impulsively, but I think it was critical that I made up my mind quickly. Why should I have gone to bed with doubts? I would wake up the next day and take the necessary steps to maintain discipline. It's important to have confidence in yourself to make a decision and to move on once you have. It's not about looking for adversity or for opportunities to prove power; it's about having control and being authoritative when issues do arise.

5. Match the Message to the Moment

When it came to communicating decisions to his players, Ferguson—perhaps surprisingly for a manager with a reputation for being tough and demanding—worked hard to tailor his words to the situation.

When he had to tell a player who might have been expecting to start that he wouldn't be starting, he would approach it as a delicate assignment. "I do it privately," he told us. "It's not easy. I say, 'Look, I might be making a mistake here'—I always say that—'but I think this is the best team for today.' I try to give them a bit of confidence, telling them that it is only tactical and that bigger games are coming up."

Observation is critical to management. The ability to see things is key—or, more specifically, the ability to see things you don't expect to see.

During training sessions in the run-up to games, Ferguson and his assistant coaches emphasized the positives. And although the media often portrayed him as favoring ferocious halftime and postgame talks, in fact he varied his approach. "You can't always come in shouting and screaming," he told us. "That doesn't work." The former player Andy Cole described it this way: "If you lose and Sir Alex believes you gave your best, it's not a problem. But if you lose [in a] limp way…then mind your ears!"

Ferguson: No one likes to be criticized. Few people get better with criticism; most respond to encouragement instead. So I tried to give encouragement when I could. For a player—for any human being—there is nothing better than hearing "Well done." Those are the two best words ever invented. You don't need to use superlatives.

At the same time, in the dressing room, you need to point out mistakes when players don't meet expectations. That is when reprimands are important. I would do it right after the game. I wouldn't wait until Monday. I'd do it, and it was finished. I was on to the next match. There is no point in criticizing a player forever.

Generally, my pregame talks were about our expectations, the players' belief in themselves, and their trust in one another. I liked to refer to a working-class principle. Not all players come from a working-class background, but maybe their fathers do, or their grandfathers, and I found it useful to remind players how far they have come. I would tell them that having a work ethic is very important. It seemed to enhance their pride. I would remind them that it is trust in one another, not letting their mates down, that helps build the character of a team.

In halftime talks, you have maybe eight minutes to deliver your message, so it is vital to use the time well. Everything is easier when you are winning: You can talk about concentrating, not getting complacent, and the small things you can address. But when you are losing, you have to make an impact. I liked to focus on our own team and our own strengths, but you have to correct why you are losing.

In our training sessions, we tried to build a football team with superb athletes who were smart tactically. If you are too soft in your approach, you won't be able to achieve that. Fear has to come into it. But you can be too hard; if players are fearful all the time, they won't perform well either. As I've gotten older, I've come to see that showing your anger all the time doesn't work. You have to pick your moments. As a manager, you play different roles at different times. Sometimes you have to be a doctor, or a teacher, or a father.

6. Prepare to Win

Ferguson's teams had a knack for pulling out victories in the late stages of games. Our analysis of game results shows that over 10 recent seasons, United had a better record when tied at halftime and when tied with 15 minutes left to play than any other club in the English league. Inspirational halftime talks and the right tactical changes during the game undoubtedly had something to do with those wins, but they may not be the full story.

When their teams are behind late in the game, many managers will direct players to move forward, encouraging them to attack. Ferguson was both unusually aggressive and unusually systematic about his approach. He prepared his team to win. He had players regularly practice how they should play if a goal was needed with 10, five, or three minutes remaining. "We practice for when the going gets tough, so we know what it takes to be successful in those situations," one of United's assistant coaches told us.

United practice sessions focused on repetition of skills and tactics. "We look at the training sessions as opportunities to learn and improve," Ferguson said. "Sometimes the players might think, 'Here we go again,' but it helps us win." There appears to be more to this approach than just the common belief that winning teams are rooted in habits—that they can execute certain plays almost automatically. There is also an underlying signal that you are never quite satisfied with where you are and are constantly looking for ways to improve. This is how Ferguson put it: "The message is simple: We cannot sit still at this club."

Ferguson: Winning is in my nature. I've set my standards over such a long period of time that there is no other option for me—I have to win. I expected to win every time we went out there. Even if five of the most important players were injured, I expected to win. Other teams get into a huddle before the start of a match, but I did not do that with my team. Once we stepped onto the pitch before a game, I was confident that the players were prepared and ready to play, because everything had been done before they walked out onto the pitch.

I am a gambler—a risk taker—and you can see that in how we played in the late stages of matches. If we were down at halftime, the message was simple: Don't panic. Just concentrate on getting the task done. If we were still down—say, 1–2—with 15 minutes to go, I was ready to take more risks. I was perfectly happy to lose 1–3 if it meant we'd given ourselves a good chance to draw or to win. So in those last 15 minutes, we'd go for it. We'd put in an extra attacking player and worry less about defense. We knew that if we ended up winning 3–2, it would be a fantastic feeling. And if we lost 1–3, we'd been losing anyway.

Being positive and adventurous and taking risks—that was our style. We were there to win the game. Our supporters understood that, and they got behind it. It was a wonderful feeling, you know, to see us go for it in those last 15 minutes. A bombardment in the box, bodies everywhere, players putting up a real fight. Of course, you can lose on the counterattack, but the joy of winning when you thought you were beaten is fantastic.

I think all my teams had perseverance—they never gave in. So I didn't really need to worry about getting that message across. It's a fantastic characteristic to have, and it is amazing to see what can happen in the dying seconds of a match.

7. Rely on the Power of Observation

Ferguson started out as a manager at the small Scottish club East Stirlingshire in 1974, when he was 32. He was not much older than some of his players and was very hands-on. As he moved up—to St. Mirren and Aberdeen, in Scotland, and then, after spectacular success at Aberdeen, to Manchester United—he increasingly delegated the training sessions to his assistant coaches. But he was always present, and he watched. The switch from coaching to observing, he told us, allowed him to better evaluate the players and their performances. "As a coach on the field, you don't see everything," he noted. A regular observer, however, can spot changes in training patterns, energy levels, and work rates.

The key is to delegate the direct supervision to others and trust them to do their jobs, allowing the manager to truly observe.

Ferguson: Observation is the final part of my management structure. When I started as a coach, I relied on several basics: that I could play the game well, that I understood the technical skills needed to succeed at the highest level, that I could coach players, and that I had the ability to make decisions. One afternoon at Aberdeen I had a conversation with my assistant manager while we were having a cup of tea. He said, "I don't know why you brought me here." I said, "What are you talking about?" and he replied, "I don't do anything. I work with the youth team, but I'm here to assist you with the training and with picking the team. That's the assistant manager's job." And another coach said, "I think he's right, boss," and pointed out that I could benefit from not always having to lead the training. At first I said, "No, no, no," but I thought it over for a few days and then said, "I'll give it a try. No promises." Deep down I knew he was right. So I delegated the training to him, and it was the best thing I ever did.

It didn't take away my control. My presence and ability to supervise were always there, and what you can pick up by watching is incredibly valuable. Once I stepped out of the bubble, I became more aware of a range of details, and my performance level jumped. Seeing a change in a player's habits or a sudden dip in his enthusiasm allowed me to go further with him: Is it family problems? Is he struggling financially? Is he tired? What kind of mood is he in? Sometimes I could even tell that a player was injured when he thought he was fine.

I don't think many people fully understand the value of observing. I came to see observation as a critical part of my management skills. The ability to see things is key—or, more specifically, the ability to see things you don't expect to see.

8. Never Stop Adapting

In Ferguson's quarter of a century at United, the world of football changed dramatically, from the financial stakes involved (with both positive and negative consequences) to the science behind what makes players better. Responding to change is never easy, and it is perhaps even harder when one is on top for so long. Yet evidence of Ferguson's willingness to change is everywhere. As David Gill described it to me, Ferguson has "demonstrated a tremendous capacity to adapt as the game has changed."

In the mid-1990s, Ferguson became the first manager to field teams with a large number of young players in the relatively unprestigious League Cup—a practice that initially caused outrage but now is common among Premier League clubs (the Premier League consists of the country's top 20 teams). He was also the first to let four top center forwards spend a season battling for two positions on his roster, a strategy that many outsiders deemed unmanageable but that was key to the great 1998–1999 season, in which United won the Treble: the Premier League, the FA (Football Association) Cup, and the UEFA (Union of European Football Associations) Champions League.

Off the field, Ferguson greatly expanded his backroom staff and appointed a team of sports scientists to support the coaches. Following their suggestions, he installed Vitamin D booths in the players' dressing room in order to compensate for the lack of sunlight in Manchester, and championed the use of vests fitted with GPS sensors that allow an analysis of performance just 20 minutes after a training session. Ferguson was the first coach to employ an optometrist for his players. United also hired a yoga instructor to work with players twice a week and recently unveiled a state-of-the-art medical facility at its training ground so that all procedures short of surgery can be handled on-site—ensuring a level of discretion impossible in a public hospital, where details about a player's condition are invariably leaked to the press.

Ferguson: When I started, there were no agents, and although games were televised, the media did not elevate players to the level of film stars and constantly look for new stories about them. Stadiums have improved, pitches are in perfect condition now, and sports science has a strong influence on how we prepare for the season. Owners from Russia, the Middle East, and other regions have poured a lot of money into the game and are putting pressure on managers. And players have led more-sheltered lives, so they are much more fragile than players were 25 years ago.

One of the things I've done well over the years is manage change. I believe that you control change by accepting it. That also means having confidence in the people you hire. The minute staff members are employed, you have to trust that they are doing their jobs. If you micromanage and tell people what to do, there is no point in hiring them. The most important thing is to not stagnate. I said to David Gill a few years ago, "The only way we can keep players at Manchester United is if we have the best training ground in Europe." That is when we kick-started the medical center. We can't sit still.

Most people with my kind of track record don't look to change. But I always felt I couldn't afford not to change. We had to be successful—there was no other option for me—and I would explore any means of improving. I continued to work hard. I treated every success as my first. My job was to give us the best possible chance of winning. That is what drove me.

-

- 4/5 Free Articles leftRemaining Register for more |

Subscribe + Save! -