Yes. I agree I'm a lunatic when it comes to books kids. But I found such a great explanation here and it's from the amazing Umberto Eco. His perspective is that he collects books which aren't a collection of books he's read but books about knowledge he wants to acquire.

I'm now starting a new collection over the past few months. Cookbooks and books relating to food and spices and history. And it's amazing to watch them and salivate (no pun intended). These are amazing books. They talk about food. How people ate. What they did. How they cooked. How they felt. And so many I haven't read. And can't wait. And will buy more books :)

Love

Baba

Lunatic Science: Umberto Eco's Library

http://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/lunatic-science-umberto-ecos-library

(via Instapaper)

Lunatic Science: Umberto Eco's Library

Topics: Umberto Eco, Book Collecting

If the 30,000 volume book collection housed in Umberto Eco's Milan apartment can be said to inspire one response, it might well be awe. Lila Azam Zanganeh, who interviewed Eco for The Paris Review described Eco's abode as "a labyrinth of corridors lined with bookcases that reach all the way up to extraordinarily high ceilings," and makes mention of the library as "a legend in and of itself." Most commonly, when a visitor is first shown the veritable universe of books that expands throughout the author's home, they can think of only one question: "have you read all of these?"

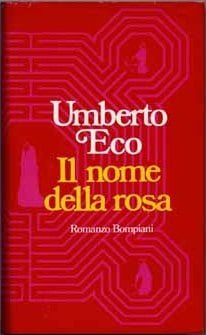

Though the question is common, it is not a particularly welcome one for Eco. Each time, he gives the same deadpan response: "No, these are the ones I have to read by the end of the month. I keep the others in my office." It is only with some rarity that a visitor remarks on the library's potential as a research tool. This, of course, is much closer to the sort of enquiry that Eco hopes for. After all, the acclaimed author of The Name of the Rose (1980) is a strong proponent of the idea that one's library should be "as much of what you do not know" as is feasibly possible. Most of what's contained within his awe-inspiring library (not to mention its 20,000 volume counterpart at his vacation home near Urbino) the accomplished thinker has yet to read, with the proportion of unread volumes increasing year after year as his reading pushes him deeper and deeper into the territory of that which he does not know.

Though the question is common, it is not a particularly welcome one for Eco. Each time, he gives the same deadpan response: "No, these are the ones I have to read by the end of the month. I keep the others in my office." It is only with some rarity that a visitor remarks on the library's potential as a research tool. This, of course, is much closer to the sort of enquiry that Eco hopes for. After all, the acclaimed author of The Name of the Rose (1980) is a strong proponent of the idea that one's library should be "as much of what you do not know" as is feasibly possible. Most of what's contained within his awe-inspiring library (not to mention its 20,000 volume counterpart at his vacation home near Urbino) the accomplished thinker has yet to read, with the proportion of unread volumes increasing year after year as his reading pushes him deeper and deeper into the territory of that which he does not know.

Eco's conception of what a personal library should be is an illuminating one. Specifically, it points to a sizable gap to be bridged in how we use the word 'library'. After all, public and university libraries offer precisely the sort of experience that Eco describes: many and manifold books containing knowledge that the inhabitant can only lay claim to a tiny fraction of. When we describe someone's personal library, on the other hand, we are almost never referring to something that has value as a research tool. Rather, personal libraries can often be testaments to the knowledge that its owner already has (or believes herself to have). By filling one's shelves with unknown knowledge, however, a personal library can become, like a public one, a place for aspirations. Whether you're researching a novel rooted in medieval history like Eco's Baudolino (2000) or simply hoping to learn new things, Eco correctly shows the way in which such a thing can be an obvious boon.

Eco's conception of what a personal library should be is an illuminating one. Specifically, it points to a sizable gap to be bridged in how we use the word 'library'. After all, public and university libraries offer precisely the sort of experience that Eco describes: many and manifold books containing knowledge that the inhabitant can only lay claim to a tiny fraction of. When we describe someone's personal library, on the other hand, we are almost never referring to something that has value as a research tool. Rather, personal libraries can often be testaments to the knowledge that its owner already has (or believes herself to have). By filling one's shelves with unknown knowledge, however, a personal library can become, like a public one, a place for aspirations. Whether you're researching a novel rooted in medieval history like Eco's Baudolino (2000) or simply hoping to learn new things, Eco correctly shows the way in which such a thing can be an obvious boon.

The question remains, of course, that if Eco hasn't read most of the books in his collection, why and how does he choose the books he chooses? Some of his collection is devoted to his own personal history. For instance, he has spent years trying to replicate a collection of the Italian travel magazine Giornale illustrato dei viaggi e delle avventure di terra e di mare that his grandfather had amassed and which Eco himself had lost in his earlier years. The strongest guiding principles of his collecting, however, have to do with his investigations into human thought. In his own words:

"As a rare books collector I am fascinated by the human propensity for deviating thought. So I collect books about subjects in which I don't believe, like kabbalah, alchemy, magic, invented languages. Books that lie, albeit unwittingly. I have Ptolemy, not Galileo, because Galileo told the truth. I prefer lunatic science."